Background Information:

These stories are biographical narrations by the author, written down around 20 years ago. This was originally meant to be published as a book, but after completing the first eight chapters, the author chose not to continue, and thus we are left with the stories in their present incomplete form. Most of these stories took place around 1970. The areas discussed in these stories have changed greatly in the last 40 years and may not match what we see today. All of these stories are factual. There is no plan to ever publish this book, so if you want to know more, or if you want to know about other events that occurred, you would have to meet the author personally.

Chapter Four

The Chandogya Upanishad relates how Indra, king of the devas, and Virochana, king of the demons, both became students of the science of self-realization under Brahma. Brahma, to test them first, told them that the self was what they saw when they looked into a mirror or a pan of water. Virochana believed and went back to become a guru, teaching this to the other demons, who also believed; but Indra had second thoughts and returned to receive the true knowledge of the self as soul.

The coming of the year 1974 saw my mind roiling with confusion. I had become a bibiliophage, a gourmand of esoteric books on everything from astrology to Zoroaster. And I’d been offered tantalizing glimpses into heightened states of awareness by beings mysterious and divine. But it all had left me fundamentally bewildered. So many paths to so many goals – which one should I dedicate myself to? Which one led to Truth?

Though I couldn’t see it at the time, the problem was the very nature of my desire to know. It is said that there are two kinds of curiosity: that for what is useful, and that for what others don’t know. Mine was the latter. I wanted not so much to know as to be known by others for knowing what they did not.

And the visitations of divinities? Even if it was true a great siddha-yogi or Karttikeya or Devi had come to me, they, like Brahma, held mirrors in their hands.

After returning to Salem, I took up the worship of Bala as the little girl in Mahabalipuram had advised. It did chasten my outlook on women. But I found it impossible to fix my mind exclusively in the Shakta discipline.

I had no doubt that worship of Devi, who carries twenty weapons representing twenty kinds of pious deeds recommended in the Vedas for subduing vices, purifies the base animalistic desire. I’d discovered this years before in Kerala. But I questioned the final goal of it all. The Devidham (place of Devi) is the material universe. It contains fourteen levels of worlds in which the souls transmigrating from species to species are confined. The goddess is named Durga (dur – difficult, ga – movement) because she imprisons these souls in matter.

The philosophy of the Shaktas is called Sambhavadarshana. The goal is to become identical to that Divine Mother who is the origin (srishti) of material existence. Everything has its support (sthiti) in her. At the time of cosmic dissolution (pralaya) everything merges into her. In Sambhavadarshana there is nothing beyond this continual cycle of creation and destruction, so there is no provision for liberation from matter. The meditation of the Shaktas is to consantly think of themselves as women, because in their view God is the original female (adyashakti).

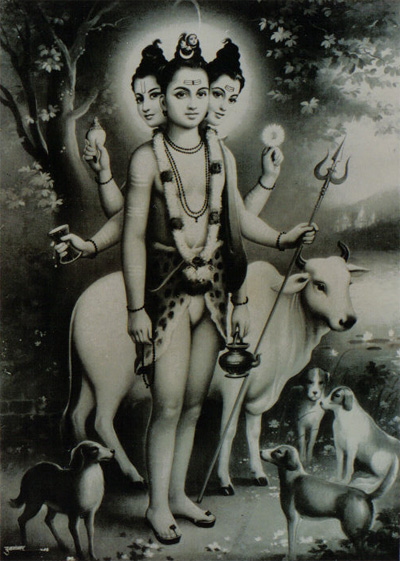

Durga has two sons, Ganesha and Karttikeya. Both are deputed leaders of Shiva’s ganas (followers); Karttikeya is specifically Shreshtharaja, the sublord of the bhutas (ghosts). Ganesha represents material success and Karttikeya material beauty. Worship of Ganesha or Karttikeya can gradually qualify one to enter Kailash, the most elevated plane of material existance, the abode of Shiva. But even here one does not surpass the cycle of birth and death. One of the great saints of Shaivism, Sundaramurthi Nayanar, is said to have taken his birth in South India after falling from Kailash due to becoming lusty for one of Shiva’s female servants.

Shiva, the master of siddha-yoga, is ever fixed in meditation upon Transcendence. Those who are austere and determined enough to follow his example may by his grace cross from Kailash into Sadashivaloka, his eternal realm forever illumined by the rays of the effulgent spiritual sky, just beyond the threshold of Devidham.

This was the path taken by Brahmendra Avadhuta, and it was surely closed to people like me. I was not prepared to meditate naked in the cold Himalayas for years together.

But many of the Advaitist books I’d read averred that realizing Brahman was not so difficult; it was all a matter of mind-set. One should conceive of the manifest world as maya, an illusion having no more substance than a dream. Hidden behind maya is the impersonal Absolute, the only reality. The central theme of Advaita philosophy is expressed by the declaration tat tvam asi, ‘you are that (Brahman).’ If I am Brahman, then the world is merely my own hallucination. By proper discrimination (viveka), I should be able to negate the world and achieve the supreme bliss of the self (ananda).

The Advaitist doctrine relies on clever syllogism to defend its theory that everything we see is really only formless Brahman. This has popularized it among those fond of speculation.

For instance, Advaitists say that the material world is a reflection of Brahman, like a reflection of the moon on water. To the objection that this analogy betrays Brahman’s formlessness because to be reflected Brahman must have form, the reply is that form should not be mistaken for substance. When we see a reflection of something, it is of the form, not of the substance itself. Thus form is distinct from substance. And because form can be reflected it is inherently illusory. Moreover, Brahman is not a substance – it is ineffable. So the rule of symmetry of comparison does not apply.

Shankara conceived of three levels of awareness: pratibhasika, complete illusion; vyavaharika, conventional or useful illusion; and paramarthika, transcendence. In complete illusion, one thinks the reflection is real. In conventional illusion, though still seeing it, one knows it is a reflection and acts to overcome it. That ultimately means one must become a sannyasi ordained in Shankara’s line and follow the strict code of monastic life prescribed by him. In the paramarthika stage, one’s sense of individual identity, the substance that gives form to illusion, is eradicated entirely. Only then is illusion vanquished. There are no words to describe the experience of transcendence, because words are also forms of the substance of false identity.

Because the means of awakening to transcendence is itself illusory, a cogent explanation of just how illusion is overcome is not possible in Advaitism. A great Advaitist scholar, Jayatirtha Muni, compared it to having a nightmare. When one is sufficiently frightened, one awakes, and the nightmare (the vyavaharika illusion) disappears.

On the vyavaharika platform the Advaitist worships the form of God (as Devi, Ganesh, Surya, Shiva or Vishnu), but with the intention of seeing the worship, worshiper and worshiped dissolve into impersonal oneness. It is sometimes said that this dissolution happens ‘by the grace of maya.’

Thus Advaitists are also known as Mayavadis. Because their perfection ultimately depends on the grace of maya, there are now many Mayavadis around the world who feel no compulsion to adhere to Shankara’s methods. If life be but illusion, then distinguishing between a monastic life and a licentious life is also vain illusion. His commentary on Vedanta-sutra, a weighty Sanskrit lucubration of dry abstractions, was traditionally required daily reading for his followers. But nowadays Mayavadi Vedantism has been reduced to trite sloganeering like ‘It’s all in the mind,’ ‘It’s all one,’ and the final twist: ‘I am God.’

While appreciating the slipperiness of some of the arguments, I found the Advaitist denouement disappointing. If my self is already identical with Brahman, then why is the realization of this supposedly universal truth limited to just a few rare souls? If I am one with those souls who have realized Brahman, why didn’t I and everyone else realize it when they did? It added up to a free lunch I couldn’t afford.

When I once expressed my dissatisfaction with Advaita philosophy to a disciple of Brahmendra Avadhuta, he sent me to a sadhu who was an adherent of the Sankhya doctrine.

There is a theistic and an atheistic form of Sankhya. The theistic Sankhya tradition begins with the Puranas and was first taught by the sage Kapila, an incarnation of Vishnu. The atheistic version is recounted in an ancient treatise called Sankhya-karika by Ishvarakrishna. He gives credit to someone also named Kapila as the inventor, though no writings from that Kapila are extant. The sadhu I met was from the atheistic school.

The word sankhya means ‘count’; Sankhya philosophy counts up the elements of reality and categorizes them within two ultimate principles: purusha (spirit) and prakriti (matter). Because it identifies these two as the opposite but complimentary factors of existence, Sankhya is free of the unintelligible solipsism that plagues the Advaita doctrine.

Prakriti gives form to the world, and purusha gives it consciousness, and both are real. In the purusha category are innumerable individual souls, called jivas, who are eternally distinct from one another. Under the influence of prakriti, they become bound by the three qualities (gunas) of goodness (sattva), passion (rajas) and ignorance (tamas). Thus they develop physical forms consisting of gross and subtle material elements and are forced to suffer the pains of birth, old age, disease and death repeatedly. But in their essence, the jivas are always pure.

The means to liberation in Sankhya is detachment. When the soul ceases to identify with the external coverings of the false ego, intellect, mind, senses and the sense objects, he is released from suffering. The means to detachment is self-analysis through yoga.

My Sankhya teacher was invited to an Advaitist ashram to engage in debate with some of their scholars. I accompanied him, and was amazed as he defeated fifteen Mayavadi sannyasis in a row. Seeing this convinced me that the Advaitist philosophy has serious shortcomings.

Further investigation of Sankhya led me to books expounding the theistic version. And here again I found two divisions: Vishishtadvaita and Dvaita, the first propounded by Ramanuja and the latter by Madhva. Both are systems of Vaishnava Vedanta in which Samkhya plays a supporting role.

In Vishishtadvaita (‘qualified monism’), the jivas and prakriti are held to be qualities (visheshanam) of Vishnu, the highest truth. Ramanuja compares them to the body, and Vishnu to the soul, of Brahman. Vishnu is therefore the only Purusha.

The jivas are classified as superior spiritual energy (parashakti), like Vishnu in quality. But they are small in potency, like infinitesimal particles of sunlight. Vishnu, their source, is the Greatest Being (Vibhu), just as the sun is the greatest light in the sky.

Matter is like a cloud. Though also generated by the sun, a cloud is inferior in energy to the sunlight; thus matter is called inferior energy (aparashakti). Matter is the cause of maya, and just a cloud blocks a portion of the sunlight, maya deludes some of the souls. But compared to the sun, maya is insignificant.

Both the souls and maya are fully dependent upon and in that way inseparable from Vishnu. He is the transcendental Lord, eternal, full of knowledge and bliss, and ever a person. In the philosophy of qualified monism, tat tvam asi (‘you are the same’) means ‘you, the individual soul, are the same in quality as Vishnu.’ But it can never mean ‘you are God.’

Madhva was implacably opposed to monism, so he boldly called his system Dvaita, or Dualism. His main target was Shankara’s Advaita, but he also took exception to certain tenets of Ramanuja’s Vishishtadvaita.

The word advaita is taken by Shankara and to a certain extent by Ramanuja to mean ‘not different.’ Madhva was strictly literal: advaita means ‘not two’ as in the sense of the Upanishadic statement eka brahma dvitiya nasti, ‘Brahman is one, there is no second.’ Dvaita philosophy thus established that God is unrivalled and aloof. He has no competitor, nor is He beholden to anyone. Therefore He cannot be bewildered by maya as the Mayavadis believe. Nor can the souls and maya be said to comprise His body, because that would imply His dependence upon them.

In other words, advaita really means ‘unique.’ God, being unique, must be distinguished from that which is under Him. But this does imply utter severance of the souls and matter from God. For example, the statement ‘the lotus is blue’ is not rendered untrue by acknowledging that the flower and the color are not one and the same. Thus Madhva’s Dvaita is not like the fundamental dualism of atheistic Sankhya. It upholds one God and one God only who is the source of everything. Dvaita indicates ‘distinction’ in the dual sense of discrimination and eminence, i.e. Dvaita distinguishes God because God is distinguished.

For the two questions I considered most important – ‘What is God?’ and ‘How do I attain God?’ – Ramanuja and Madhva gave identical answers: Sri Vishnu is God and is attained by bhakti (pure devotion of the soul). Both further agreed that liberation is never wrested by the strength of the jiva’s knowledge or detachment, and it is certainly not awarded by matter. Liberation is granted by Divine Grace, and is not confined to those who make effort to receive it. And liberation is not merely the cessation of suffering. It is a state of positive spiritual bliss obtained through association with Vishnu, the All-Blissful.

I thought the Vaishnava teachings were easily the purest of the philosophies I’d covered. But I had my reservations. Foremost was the fact that I found the other doctrines more accessible. Without much endeavor I was able to master Shakta, Shaiva, Advaita and atheistic Sankhya to the point where I could easily pass as an authority. But whenever I read the Vaishnava texts, I felt like an outsider looking in. It just didn’t fit my mentality.

Another doubt arose from the visits I’d made in my life to Vaishnava temples. I couldn’t see anything in the priests or the faithful that really distinguished them from the general mass of pious, ritualistic Hindus. I’d read the biographies of Ramanuja and Madhva, and I believed they were ideal saints and teachers. If I’d met Vaishnavas like them, it would be much easier to accept their fine philosophical conclusions. But from what I’d seen, the Vaishnavas were just another orthodox Hindu community going about their everyday lives.

The sampradayas or schools of Ramanuja and Madhva upheld the Hindu tradition of Brahmanism by birth. To be sure, the Vaishnavas admitted that a man, woman or child of any caste or even no caste could be blessed by Divine Grace. But it was only the Brahmins who by birthright were the special servants of Vishnu in this world. They alone were pure by nature and thus entitled to perform the temple rituals. This smacked of elitism, and I didn’t like it.

It appeared that Vishnu Himself didn’t always like it either. Ranganatha, the Vishnu murti at the temple of Rangakshetra in Trichy, is said to have locked the head priest out of the sanctum sanctorum because he had abused Tiruppan Alvar, a Vaishnava saint from the pariah caste. The murti refused to open the door until the priest carried Tiruppan into the temple upon his shoulders.

Andal, another famous Vaishnava saint, was a young girl who stepped boldly into the sanctum sanctorum to accept Ranganatha as her husband. As a class, women are considered ritualistically impure and are not permitted to enter the altar of the murti. But Vishnu does not care for ritualistic purity as much as pure devotion. Andal was miraculously absorbed into Ranganatha and is honored today as an expansion of Lakshmi, the feminine personification of Vishnu’s spiritual potency.

I decided to just suspend belief in all these doctrines and go on with my search for a direct experience of transcendence by which I’d know intuitively which philosophy, if any, was true. But to impress others, I used to assume these standpoints rhetorically. If I happened to meet a Shakta, I might speak like an Advaitist. Or with an Advaitist, I might argue Sankhya. Like the Muslim who became an infidel while hesitating between two mosques, I was a general disappointment to everyone.

My book-buying stops at the Shivananda Yoga Mission had gotten me on friendly terms with with the director, a calm, sober and well-spoken fellow a few years my senior. He disapproved of my eclecticism and argued that to make progress on any path, I had to first take up the prescribed sadhana.

“By reading books you simply grasp the tail of the eel of enlightenment. It will ever slip away from you,” he told me in gentle, measured tones. “Better you stick to one thing and perfect it. I can teach you a daily program of yoga that will help you to concentrate your mind on the inner light. You will become peaceful, and where there is peace, there is God.”

I tried, but my mind was too damned restless to maintain it.

When I met him again and confessed my inability to keep up the program, he closed his eyes for a moment in thoughtful silence. Then he opened them, but kept his gaze lowered as he spoke.

“The single-minded animal is captured by its deadly enemy because its actions are predictable. But a man of many minds is captured because of his unsteadiness.” He paused, then fixed his eyes on mine as he spoke again. “Do you know what man’s deadly enemy is?”

“No,” I answered in a small voice.

He quoted the Bhagavad-gita: “It is lust only, Arjuna, which is born of contact with the material modes of passion and later transformed into wrath, which is the all-devouring, sinful enemy of this world.”

Parts in this series:

Chapter 1: Exposure to the Tantric Path

Chapter 2: Secrets of Left-hand Tantra

Chapter 3: The Gate of Dreams (Tantrics of Kerala)

Chapter 4: The Self in the Mirror

Chapter 5: Again a Mouse

Chapter 6: I become ‘Swami Atmananda’

Chapter 7: With and against Sai Baba

Chapter 8: Odd Gods of the South

Background information: These stories are biographical narrations by the author, written down around 20 years ago. This was originally meant to be published as a book, but after completing the first eight chapters, the author chose not to continue, and thus we are left with the stories in their present incomplete form. Most of these stories took place around 1970. The areas discussed in these stories have changed greatly in the last 40 years and may not match what we see today. All of these stories are factual. There is no plan to ever publish this book, so if you want to know more, or if you want to know about other events that occurred, you would have to meet the author personally.

i have fallen short of words , thanks a lot for the article , well i guess i could comprehend till here , a bit nervous to read on the next one .

very lucid and clearly explained.

This is one of the best articles on different schools of thought.The author seems to be an elevated soul.

Difficult to absorb all of it but definitely it is the mind that is supreme as it can acts as a channel to one’s soul and has to be in its purest form which is possible only after knowing what’s impure. Thanks for this article as it helps people like us who are not connected with the spiritual world outside of the internet.

enlightening,very enlightening,i was doing ok,with whatever i was following and practising.but now the quest for knowlege has been ignited,and i do not know,when my thirst is going to be quenched.

How can i contact the author? I am so eager to talk to him about other events he encountered after the visit to Himalayas.

First attain the pervasiveness in the space through silent prayer or meditation. Like patanjali said, ” it is easy for the diligent. Then it is easy to see which path is true. Just as it has been said , “there is nothing higher than samkhya.” Why? Because there is nothing higher than, knowledge of the difference. Between what you are and what you are not.

Aquinas said that knowing depends on the knower. A table is a piece of furniture for me but a safe abode for a microbe living thereon. Human mind is no screen that gets imprinted with images thrown at it, but it comprehends and analyses before it absorbs. What it absorbs depends on what it possesses ab initio

I liked these words very much

where there is peace, there is God

I enjoyed reading it until the previous chapter. This is an inflection point, where the author, who seemed intelligent until now, is deflected towards ego-boosting, self-righteous organizations like ISKCON and it’s vulgar terms to describe devatas and realized beings of Sanatana Dharma. A clear example of a more than oridinary soul on it’s search for path to the Truth, falling to clutches of the popular movements of the day. Sorely disappointed. I found this website yesterday and enjoyed some of the articles until now. No more.