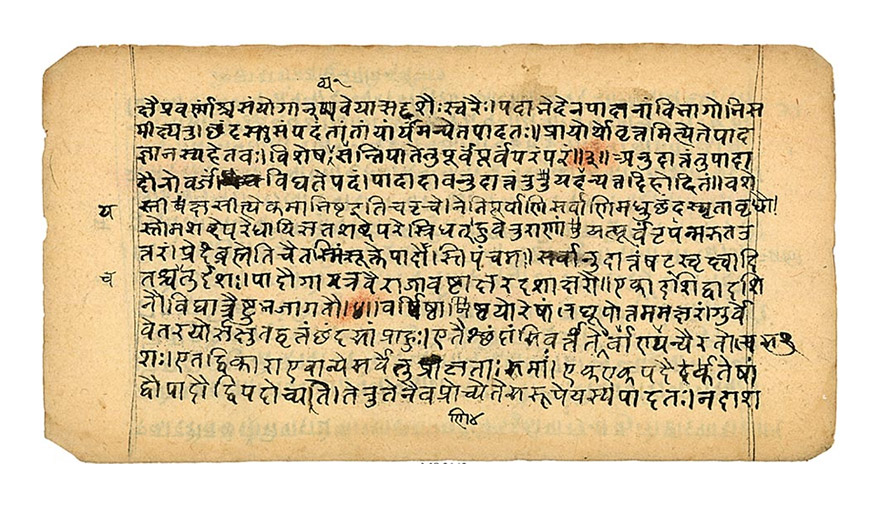

Upaniṣads are treasures of Indian spiritual thoughts of ancient times. The ten most ancient Upaniṣads belong to the period of 1500 BC to 600 BC, according to commonly agreed estimations. They are called the Principal Upaniṣads and are considered to be the most authentic ones.

There is another Upaniṣad by name Śvetāśvatara Upaniṣad belonging to a later period, but viewed at par with the Principal Upaniṣads, considering the dexterity and erudition with which the subject matter is dealt with therein. In this discussion whenever we refer to Principal Upaniṣads, it may be understood to include Śvetāśvatara Upaniṣad also. There are many other Upaniṣads written during later periods, the total number being 108 according to some, while others put the number at 200 plus. But in the present discussion we consult only the Principal Upaniṣads.

[wp_ad_camp_1]

All the spiritual thoughts of ancient India which got accumulated through ages were existing in a single lump without any orderly arrangement or classification. It was Sage Vyāsa who successfully classified all into a proper order on the basis of specific topics dealt with in each piece and their comparative importance. This is how we got the four Samhita-s, the Brāhmaṇa-s, the Āraṇyaka-s and the Upaniṣad-s. Samhitas are mostly hymns for praising or invoking various gods for well-being and favours. Brāhmaṇas and Āraṇyakas mainly deal with ritualistic illustrations of the Samhitas. Upaniṣads represent philosophical postulations either extracted from these three or compiled independently. Of the eleven Principal Upaniṣads, one (Īśa Upaniṣad) is part of a Samhita (Śukla Yajurveda), four (Bṛhadāraṇyaka, Chāndogya, Kaṭha, Kena) are parts of Brāhmaṇas and two (Aitareya, Taittirīya) are parts of Āraṇyakas. The remaining four (Praśna, Muṇḍaka, Māṇḍukya of Atharva veda and Śvetāśvatara of Kṛṣṇa Yajurveda) are independent compilations. Why should the same contents of an Upaniṣad find a place in some Samhita, Brāhmaṇa or Āraṇyaka? Because the same text contains certain portions that qualify for inclusion in the Upaniṣad and some other portions suitable for Samhita, Brāhmaṇa or Āraṇyaka. While studying the Upaniṣads we have to make due allowance for this fact.

Upaniṣads are not like ordinary spiritual texts which dwell on glorification and appeasement of an almighty god through prayers, rituals and offerings with an intention to secure protection, prosperity, happiness and long life. The primary concern of Upaniṣads is not the physical life as such, but the ultimate principle that sustains the physical life. Upanishads recognize the existence of an entity beyond the phenomenal world. They advance the concept of reality from a relative plain to the absolute state, to the reality that is free from all limitations of time and space. This advancement is the greatest achievement that Indian meditative mind accomplished and it is the greatest ever height that human mind scaled in speculative thinking. It was with this advancement that, in India, mere spiritual thinking graduated into pure philosophical deductions.

It is therefore imperative that any attempt to understand the teachings of Upaniṣads must be with due consideration for this unique feature inherent in them. Any alternative attempt employing the traditional tools of interpretation is unwelcome as it would only obscure the scientific spirit of the Upaniṣads and degrade their sublime teachings to mere theological compositions. Moreover, being extracts from other three parts of the Vedas, most of the Principal Upaniṣads contain some portions that do not fit well with the main theme under discussion in that particular Upaniṣad. Therefore, while interpreting the Upaniṣads to derive lessons therefrom, these portions have to be omitted from detailed consideration. In the present endeavour we keep in mind these observations as a guide in explaining the contents of each Upaniṣad. That means, we concentrate on those teachings that a rational mind should take note of and assimilate into its own cognitive constitution; in this process we simply ignore those contents which are rather ritualistic or purely mythological in nature.

With these words let us approach the Upaniṣads one by one for enlightenment. In this endeavour we take up only the eleven Principal Upaniṣads mentioned above.

Readers can contact the author by email at: karthiksreedhar@gmail.com

[Editor’s note: In following articles the author will present an analysis of each of the 11 main Upanishads.]

Prior articles in this series:

The Science of the Upanishads – Introduction

The Science of Brihadaranyaka Upanishad

The Science of Chandogya Upanishad

The Science of Ishavasya Upanishad

The Science of Katha Upanishad

The Science of Kena Upanishad

The Science of Mandukya Upanishad

The Science of Mundaka Upanishad

The Science of Prashna Upanishad

The Science of Taittiriya Upanishad

The Science of Aitareya Upanishad

The Science of Shvetashvatara Upanishad

The Science of Upanishads – Conclusion

very nice ..

The Article was informative. Greatly appreciated. Only thought that might need a consideration was illustrating the pointers.

It is unfortunate that in this good article the Author unnecessarily mentioned arbitrary dates for the Upanishads. Let us honour our tradition that Vedas are timeless and sacred. With such reverence only we should approach a study of Vedas. The moment we think it is authored by someone, we will lose the high degree of substance Vedas possess. We will only then look at mere words and try to translate, like Max Muller did, and will miss the theme.

Excellent so nicely explained

indeed a great service to talk about principal upnishads

Namaste,

Very informative and very interesting. May you be blessed to continue publishing details of Upanishads.

Ramnath

Our ancient Rishis did not stop with the study of our physical body of our human personality. Through their meditation, seeking and contemplation they studied the MIND and went beyond the mind and realized some truth about our life & cosmos, which they sang in the songs of Upanisheds. They are indeed Great works.

respected sir

this is very exciting and very good

ram

Agree with Mr saranathan Comment.

Very unfortunate, the author puts a date to vedas, which are timeless as it says even after maha pralayam which occurs on when 100 years of brama is completed. That period is apprx 40lacs earthly years of 4 yugas x140times of each day of bramahax365 daysx100 years. So to limit in bc is reducing its status. Also Upanishad part of vedas are found are extracted by rishis, who are called mantra drishta- means the one who found the mantra and revealed. Like visvamitra rishi found Gayatri mantra which existed, he found and revealed. There are millions of upadnishads and veda mantra are in the form of sound wave. if we have thapas and austrieity and divine grace, we can also extract. pl if not glorify, we do not misinform people.

I hope the author will explain and continue more of Upanishads to read in the coming days

Very good, but Saranathan has a very strong point.

This is Golden Treasure of knowledge made available to us by our Maharshis.They provide us solutions of our all problems and are “MARGDARSHAK” for our lives.

Roop R.Sharma

It is an excellent brief summary about Upanishads for Western mind! I agree with few of the comments above, that Vedas are supremely sacred for Hindus, and are timeless in origin. We just had an article last week,on the same website, stating Vedas are more than 10,000 years old! ( with scientific proof ) We should not cultivate the old habit of catering to Western Indologists. We cannot change them,unless we change our own beliefs.

Here the list of 10 largest Hindu temples in the world.

5 Belur Math, Kolkata, India, 40 Acres.

4 Thillai Nadaraja Temple, Tamil Nadu, India, 40 Acres.

3 Akshardham, Delhi, India, 100 Acres.

2 Sri Ranganathaswami Temple, Srirangam, Tamil Nadu, India, 156 Acres.

1 Angkor Wat, Cambodia, 500 Acres.

Very Informative.

i am proud of my ancestors but we have not fallowed we are in race with western living……

Of Veda it is said it is Apaurusha and Ananta. What is apaurusha? It is not compiled by a purusha who normally operates in this world with his thought process which in intrinsically different form thinking mechanism. Thinking is always is in the present it has no past or future, whereas Thought is a dead thing which is again and again revived by you and me. The Angirasa Rishis (10 of them) who compiled Veda were able to transcend the thought process and became one with Consciousness (so Angirasa-essence of flame). The compilation is also Ananta, timeless. In a later period, the date is not of such great importance thought based men created Vedanta based on Upanishads. Whether the Rishis of Upanishads were of the same cadre as Angirasa Rishis is indeed important.

Very good vital information to know Thank you very much

This is a nice introduction to Upanishads. Many intelligent and cunning people have altered ancient Indian records to distort and and create a wrong message so that Indians be ignorant of their own great past. Vedas and consequently the Upanishads are prehistoric and it it incorrect to date them to a little before Christ. Many pieces of recent writings have been unjustly named as Upanishads lika Allah Upanishad, Christ Upanishad, etc.You do not know which line among what you are reading, of our scriptures, has been deliberately thrust with malafide intentions. One Pandit told me an unknown person who called himself “Ravana” had interfered in Hindi Scriptures and interpolated some stazas that would through doubt or confusion into the readers’ minds.

Let us be discriminatory in this aspect.

With this good introduction, let us study the summary of Upanishads and take the correct path.

Eswara is Brahmaveda Swarupam. Eswara is Ajam(without birth)

Eswara is infinite in time and space. As such no dates would be applicable to Vedas/Upanishats.